It is African-American History Month again. Having spent the last two weeks dwelling on foreign affairs 100 years ago, it's high time to turn to domestic affairs — particularly, the growth of the Ku Klux Klan.

|

| "A Blot on the Escutcheon" by Elmer Bushnell for Central Press Assn., ca. Jan. 3, 1923 |

We'll start with a Klan lynching that attracted national media attention — quite possibly because the victims were white.

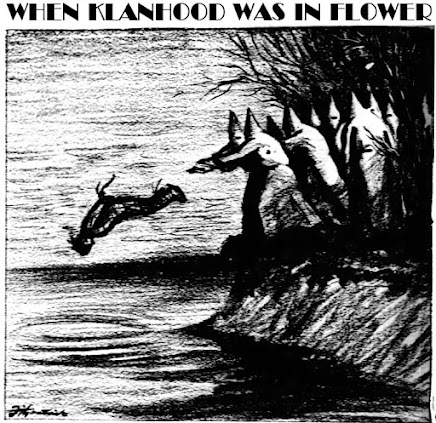

In August 1922, members of the Ku Klux Klan tortured and killed Filmore Watt Daniels and Thomas Fletcher Richards. (Some accounts omit "s" at the end of both last names; I'm using the names from contemporary newspaper reports.) Daniels was the adult son of a wealthy landowner in Mer Rouge, Louisiana, a town near the Arkansas border; he and his father were vocal opponents of the Klan. Richards, a mechanic, was a good friend of the younger Daniels.

The Danielses, father and son, were returning home with Richard and two others from a ballgame in nearby Bastrop when they were stopped by heavily armed, black-hooded men. The five were blindfolded and abducted to a remote site where they were whipped and beaten for information on the location of another person. Their captors released the elder Daniels and the other two men; but the younger Daniels and Richards were tortured and killed, and their bodies dumped in Lake Lafourche.

|

| "When Klanhood Was in Flower" by Daniel Fitzpatrick in St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Dec. 28, 1922 |

After their bodies were discovered on December 22, Louisiana Governor John M. Parker sought help from the U.S. Department of Justice in suppressing Klan violence within the state.

|

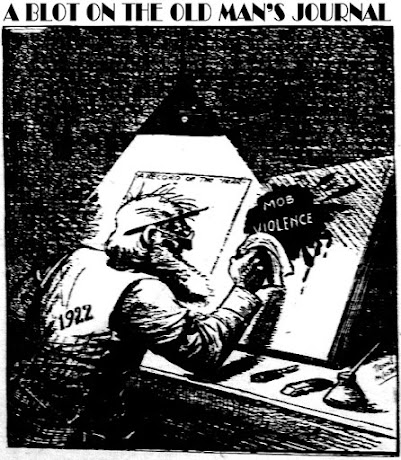

| "A Blot on the Old Man's Journal" by Dennis McCarthy in New Orleans Times Picayune, ca. Dec. 29, 1922 |

If the meaning of Times Picayune cartoonist Dennis McCarthy's December 29 cartoon left any doubt what sort of "mob violence" was a blot on Old Man 1922's journal, his front page cartoon on January 9 was explicit.

|

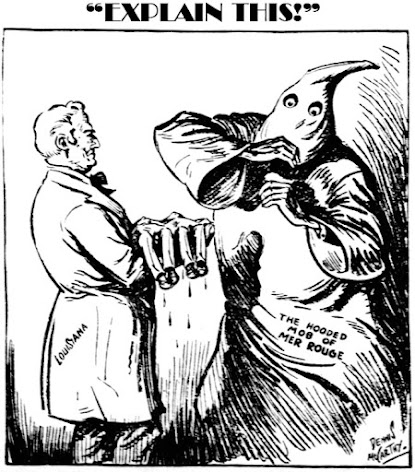

| "Explain This" by Dennis McCarthy in New Orleans Times Picayune, ca. Jan. 9, 1923 |

Reaction by members of the Klan differ from that depicted by McCarthy, according to the Shreveport Times, of January 7:

Publication of the membership of the Morehouse klan 34 Knights of the Ku Klux Klan excited only passing interest here. Most of the charter and later membership were already known. The list included many of the many of the best-known and most substantial business and professional men, farmers, and officials of the parish. And the most pungent comment regarding it was, "why didn't they print the whole list, I felt slighted because they didn't have my name."

Prominent in the list was the name of J. Fred Carpenter, who happens to be the sheriff of Morehouse. The sheriff does not appear to be bothered that anyone should know he is a klansman.

"Resign?" he was asked.

"Not yet."

"Going to?"

"I hadn't thought of it."

|

| "Mer Rouge (Red Sea)" by Daniel Fitzpatrick in St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Jan. 7, 1923 |

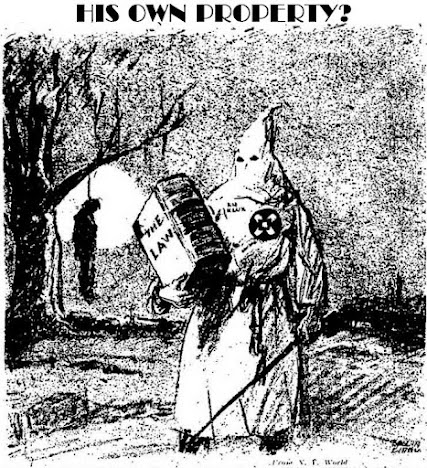

Other klansmen unmasked by the probe included a former mayor, the district attorney, the local postmaster, and a town marshal. The testimony of former klansman "Big Jim" Norsworthy exposed several locals as members, but in the end proved to be more flash than fire.

Meanwhile, Captain J.K. Skipworth, "exalted cyclops of the Morehouse klan" held court outside the courthouse to make sure that the media and anyone else in the vicinity could hear his opinion of the goings on inside.

There were klansmen in the grand jury, too. As a result, kidnapping and murder charges against named klansmen were dropped for "insufficient evidence." Even the minor charges against 17 men were dropped while the accused sheltered themselves out of state.

By the end of 1923, the judge in the case had lost his reelection bid, and Governor Parker had retired.

|

| "His Own Property" by Rollin Kirby in New York World, before Jan. 26, 1923 |

At the same time that investigative hearings were underway in Louisiana, a White mob burned the predominantly Black city of Rosewood, Florida, to the ground on January 8, 1923. Six Black Americans and two White rioters were killed. and the rest of the city's population fled by train.

|

| "With Loose Rein" by Rollin Kirby in New York World before Feb. 4, 1923 |

As was usually the case in these pogroms, a White woman claimed that she had been assaulted by a Black man. The assault allegedly occurred on New Year's Day; enraged White mobs, bolstered by a Klan rally in nearby Gainesville, descended on Rosewood on January 4.

White mobs sought out one suspected Black man, then another, then turned their rage against the whole town. First setting fire to churches, they then began setting fire to homes and shooting at the residents as they tried to flee. White merchant John Wright sheltered some people in his home; others hid in the swamps outside of town.

|

| Anonymous (Watson?), for Watson Studio, in Baltimore Afro-American, Feb. 23, 1923 |

It will come as no surprise that although a grand jury was convened in February, 1923, nobody was ever charged with a crime of any kind in the Rosewood massacre. Nor will you be shocked to hear that it wasn't until 76 years later that any of the survivors received any compensation for their losses.

As for the nation's editorial cartoonists, when it came to addressing current events from their drawing boards, white riots and klan terrorism were just one issue out of many.

|

| "The Three (Dis)Graces" by Elmer Bushnell for Central Press Assn., ca. Jan. 24, 1923 |

Even though these were only two klan/mob attacks among over 50 of them in 1922, many of the nation's cartoonists never even broached the subject at all in January or February, or at least never got an idea past their editors. On the other hand, every single editorial cartoonist at some point in January put out at least one cartoon satirizing Emile Coue's mantra of "Every day, in every way, I'm getting better and better." (Coue was the Stuart Smalley of his day.)

✍

When your humble scribe started writing this essay several days ago, Blogger, the host of this site, began posting the following notice at the top of my post list screen:

I can't say whether Blogger's content monitoring bots flagged this week's essay as possible hate speech, or if Blogger management is cowering in fear of southern Republican politicians who have been cracking down on history lessons that make bigots feel bad.

To those of you brave enough to click past whatever content warning Blogger threw up at you, thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment