When we left off last week's review of American cartoons from January, 1923 about France and Belgium sending troops into Germany to take control of the mining and lumber industries in the Ruhr valley, I promised some German cartoons this week. Given that the German mark had become practically worthless (we'll get to that later), whereas the country's industry had emerged from World War I essentially unscathed, the French government decided to confiscate whatever Germany had of value.

And not just coal and wood.

|

| "Frankreich Fordert 60000 Tonnen Stickstoff" by Karl Arnold in Simplicissimus, Munich, Jan. 24, 1923 |

As you might expect, German cartoonists were none too pleased with their French overlords.

Karl Arnold's cartoon refers to reports of declining birth rates in France. The same, however, was the case in Germany, as well as Great Britain, Belgium, and Italy. A brief baby boom immediately after the armistice was declared was followed by a decline in each of these countries almost every year through the end of World War II.

|

| "Die Friedens-Sabotage" by Werner Hahmann in Kladderadatsch, Berlin, Jan. 7, 1923 |

German cartoonists followed their government's lead in blaming France for derailing the peace process. Germany also hoped for relief assistance from the United States. French diplomacy probably didn't play as large a part in holding up American relief as did Republican isolationism.

|

| "Clemenceaus Rückfehr aus Amerika" by Hans-Maria Lindloff in Kladderadatsch, Berlin, Jan. 7, 1923 |

But this was at a time when French elder statesman Georges Clemenceau returned from a lecture tour in the U.S. A main focus of his speeches was his argument against American isolationism (but also a plea for leniency in expecting France to repay U.S. war loans any time soon). His tour did little to alter U.S. policy.

|

| "Der 'Grosse Vater' in Washington" by Arthur Johnson in Kladderadatsch, Berlin, Jan. 7, 1923 |

Coming off years of scathing cartoons of Woodrow Wilson, Arthur Johnson, half-American himself, held some hope that Warren Harding would hold to a more neutral European policy than his predecessor. His cartoon here continues a centuries-long motif of European cartoonists depicting the U.S. with Native American imagery. In this case, the transoceanic calumet is apt; keeping such a long pipe lit is no mean feat.

The smoke from the pipe spells out "Anleihe," which Google translates as "Bond."

|

| "Die Grosse Täuschung" by Eduard Thony in Simplicissimus, Munich, Jan. 10 1923 |

I'm fairly certain that the bushy-eyebrowed character on the right is President Harding, although I can't identify the skinny woman with the broad hat.

|

| "Das Almächtige Gold" by Olav Gulbransson in Simplicissimus, Munich, Jan. 10, 1923 |

International reparations conferences, including one organized by investment banker J.P. Morgan the previous June, failed to come up with any useful program for making Germany able to pay what the Entente powers demanded. Meanwhile, the German Reichsbank was desperately buying foreign currency, sinking the value of the mark and driving inflation to dizzying heights.

|

| "Die Falle" by Erich Schilling in Simplicissimus, Munich, Jan. 10, 1923 |

My German is not very good; I've translated the poem accompanying Schilling's cartoon as literally as possible, rather than attempting to imitate the verse. I have undoubtedly mangled a metaphor or two.

|

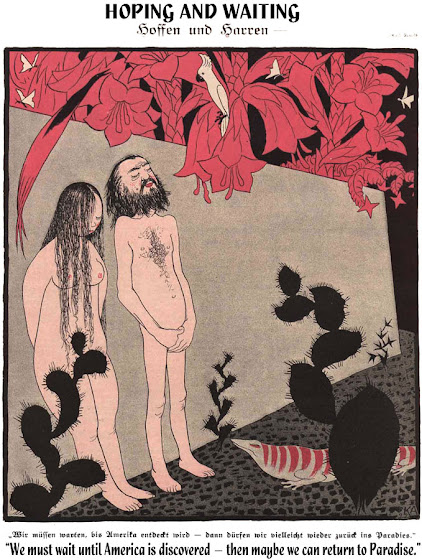

| "Hoffen und Harren" by Karl Arnold in Simplicissimus, Munich, Jan. 17, 1923 |

So that will have to suffice for now. Until next time, let us wait patiently with Adam und Eva (he having recovered nicely from his recent paidakiectomy).

No comments:

Post a Comment