My cartoon for Q Syndicate this week featured the return of Brittney Griner and a character meant to be her Russian lawyer. When I first introduced Товарищ Юрист, I remarked that I had some difficulty figuring out how to get across visually that he, a fictional character, was meant to be Russian, and not, say, an American consular official.

Back when I was a junior high school student showing an interest in cartooning, my dad enrolled in Palmer Martino's class in cartooning at the local technical college for the specific purpose of allowing me to tag along. In one of the books for the course, this was how you are supposed to draw a Russian:

|

| Detail from Cartooning the Head & Figure by Jack Hamm. Grosset & Dunlap, 1967 |

Clearly, Mrs. Griner's lawyer would not be showing up at her prison or in court looking like that guy.

If one looks instead to the movies, there were Dr. Zhivago (portrayed by an Egyptian), the Russian ambassador in Dr. Strangelove, (Peter Bull, a Brit), the crew of the submarine in Red October (led by a Scot), and Vladimir Ivanov in Moscow on the Hudson (Mork from Ork). None of them look like Jack Hamm's drawing, either, so let's turn back to cartooning:

|

| "Samson et Delilah" by Pierre-Georges Jeanniot in Le Rire, Paris, ca. June/July, 1917 |

At the time of the Russian revolution, cartoonists' stereotypical Russian was the fellow with the gun in this cartoon. The French called him Moujik (from the Russian word мужи́к, peasant.) There are various transliterations in English; I'm going to stick with M. Jeanniot's spelling today.

|

| "Sharpening the Rusty Sword" by John Cassel in New York Evening World, June 23, 1917 |

Here's an American cartoonist's version of M. Moujik.

In the popular imagination circa World War I, the typical Russian wore his hair long, and perhaps unkempt — or perhaps neatly combed, as in this cartoon by Dutchman Louis Raemaekers.

|

| "A Poison Gass Attack on New Russia" by Louis Raemaekers for Philadelphia Public Ledger Co., ca. July, 1917 |

More common, or at least more durable, in the American imagination was this older moujik by Ted Brown:

|

| "Set 'em Up Again" by Ted Brown in Chicago Daily News, Nov. 10, 1917 |

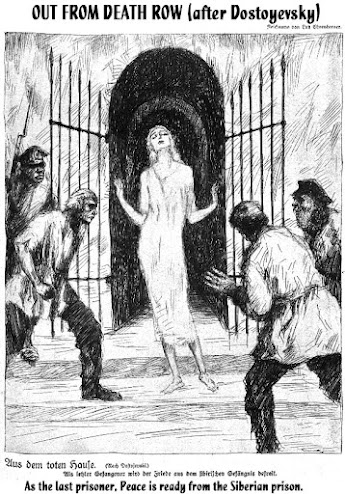

German cartoonist Lutz Chremberger offers us four versions of M. Moujik; at that particular moment during World War I, Germans anticipated that Russia's February Revolution would necessitate the Kerensky government withdrawing from the war.

|

| "Aus dem Toten Hause" by Lutz Chremberger in Lustige Blätter, Berlin, March 16, 1917 |

At the same time, Germans had another, more menacing version of M. Moujik. Another Lustige Blätter cartoonist portrays the revolutionary Duma as a doll not to be messed with.

|

| in Lustige Blätter, March 16, 1917 (?) |

This less charitable characterization is dominant in German cartoons during World War II, even when trying to minimize him.

|

| "Dies Kind, Kein Engel Ist So Sein" by Hans-Maria Lindloff in Kladderadatsch, Berlin, Feb. 1, 1942 |

By the end of the war, as the German army is falling back all across the eastern front, Herr Moujik has bulked up considerably — he is even more menacing than Tsar Nicholas's plaything.

|

| "Die Geöffnete Tür" by Ernst Schilling in Simplicissimus, Munich, Aug. 30, 1944 |

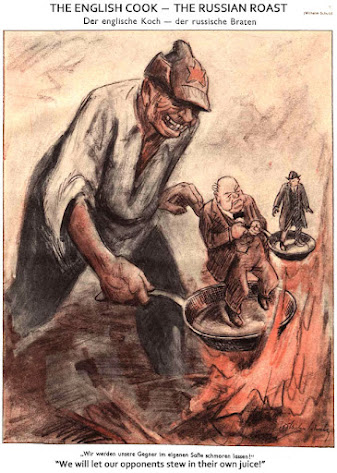

I notice, however, that he has lost his mop of hair. Just to confirm his new haircut, here's another from the late days of the war:

|

| "Der Englische Koch..." by Wilhelm Schultz in Simplicissimus, Munich, Sept. 13, 1944 |

Contrast the brutish, balding German Moujik with one from the United States, an ally for the time being:

|

| A Fourth for Bridge" by Melville Bernstein in PM, New York, Oct. 8, 1944 |

By this point, Moujik was something of a rarity in American cartoons. Russia was far more often represented by Josef Stalin or, if one was hesitant to portray Russia in a positive light, this old stand-by:

|

| "He Hibernates Long..." by Carey Orr in Chicago Tribune, Jan. 22, 1945 |

In this case, the bear is a propos; neither Moujik nor Stalin was known for habitual hibernation. As a symbol, the Russian bear goes way back, possibly to the 1500's. I do find the gratuitous "Br'er" in Carey Orr's cartoon a bit curious; but, having spent some time cartooning in Tennessee, allusions to southern folklore prolly came a tad natural-like to him.

|

| Excerpt from "Suffern on the Steppes" in Pogo Peek-a-Book by Walt Kelly. Simon & Schuster, 1955 |

Speaking of Southern stuff, let's move along to our Cold War depictions of Russian folk with this example from Walt Kelly.

For "Suffern on the Steppes, or 1984 and All That," Pogo cartoonist Kelly shifted his characters from the Okefenokee to the Soviet Union for a tale drawn expressly for a comic book. To do so, he simply drew Pogo, Howland, Albert, Churchy and Beauregard in Russian costumes. He tossed in some 1984-style revisionist dialectic, a round of Russian roulette, and the occasional onion dome in the background, and Так! We're in Russia, Comrade!

|

| "Bootstraps Gorbachev" by Pat Oliphant, July 22, 1991 |

By the sunset of the Soviet Union, Pat Oliphant's M. & Mme. Moujik were his prevalent image of the common tovarisch. Gone are Moujik's flowing locks, and hers are tucked safely away under her babushka. For all the reports in the West of bare grocery shelves, he and she nevertheless appear not to be starving.

I guess those bootstraps must be pretty filling after all.

Still, none of these images strike me as being quite right for my Russian lawyer character.

So let me rummage through my own cartoons for inspiration. Ah, here's a Russian couple my generation grew up with!

|

| for Q Syndicate, July, 2013 |

Pish posh. We all knew where Pottsylvania really was.

No comments:

Post a Comment